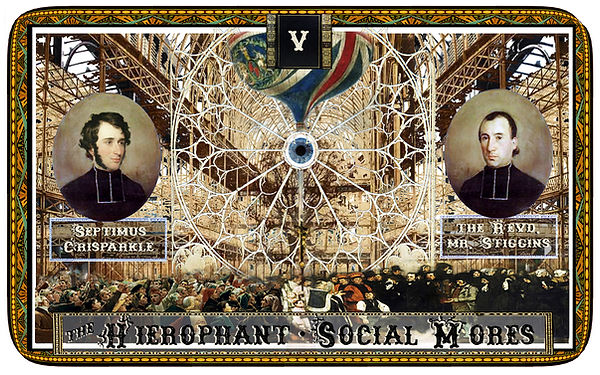

The Hierophant V Social Mores

Roman à Clef:

George W. Robinson

Characters:

Canon Septimus Crisparkle;

The Reverend Mr. Stiggins.

Books:

The Mystery of Edwin Drood;

The Pickwick Papers.

The Great Exhibition of 1851, at the midway point of the 19th Century, was the first of many international World Fairs still held to this day. Organized in part by Queen Victoria's husband, Prince Albert, the exhibition was ostensibly held for all the countries of the world to present their various achievements. In actuality, it was a showcase for England to display how its superiority in every area of industry and technology contributed to its superiority in all other fields, including moral and physical health, law, and social well-being. Six million people attended, including Charles Dickens, and with the revenue was founded The Royal Albert Museum, the Science Museum, and The Natural History Museum.

A special glass structure known as The Crystal Palace - its name coined by Dickens' good friend, the playwright Douglas Jerrold - was designed by Joseph Paxton, with its construction overseen by Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Three times the size of St. Paul's Cathedral, housing trees and over-sized statues, The Crystal Palace emphasized industrial grandeur and came to symbolize the wonder and majesty of the age. This vast vitreous structure, itself a cathedral to the British way of life, suggests the proverb: People who live in glass houses shouldn't throw stones.

Many foreigners who came to Hyde Park to visit The Crystal Palace were also shocked by the country's economic disparity and the appalling conditions of London's poor. The industrial miracle the Great Exhibition's transparent facade advertised obscured from view the grimy faces and black lung of its coal mines and child labour. “The Great Social Evil” - as prostitution came to be called - was the result of poverty and rampant in Great Britain's capital, with most of the women married, widowed, or much younger than legal marrying age. Critics derided London slums as centres of sinful co-habitation, but modern data collation shows Victorians “living in sin” numbered below 5%, compared to 9 of 10 newlyweds cohabitating in modern day Britain.

In the same year as the Great Exhibition, a poll was conducted to determine church attendance and the result startled Anglican church officials: of 18 million people, only 7 million attended Sunday service – and half of these were Nonconformists. The repercussions of this saw a reformation in the Church of England and other religious bodies, a more direct involvement with social causes such as the Temperance movement, and the formation of charities and aid organizations - the most exemplary being the Salvation Army.

Charles Dickens, for his own part, had always been a proponent of the Church of England – more the result of his John Bullishness than any alignment of spiritual doctrine. That he wrote The Life of Our Lord for his young children may be seen in the same light as the other simplified historical recap he dedicated to them: A Child's History of England. With no patience for dogma or high church piety, Dickens' religiosity can be summed up in the story of the Woman Taken in Adultery and the parable of The Good Samaritan.

Speaking of the latter and Great Britain's Great Social Evil, Dickens depicted in his fiction Nancy, a “fallen woman” capable of moral probity, and through his work with Urania Cottage, helped lift such women out of this ruinous way of life. Yet, as a man of his era, he also partook of his era's hypocrisy and double standard, patronizing houses of ill repute himself. He said of his son Charles that if the boy didn't do the same, he would consider there something wrong with his manliness.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, and perhaps his era as a whole, Dickens did not believe morality to be mastered by class and caste. Rather, morality - along with faith and redemption - was a matter of private courage and virtue which held morality master over class and caste. With his moralizing and marked penchant for preaching a sermon, Dickens could be conventional, reactionary, and even orthodox. He recommended, for instance, perpetual imprisonment for “street-corner loiterers” and once took a young girl into custody, insisting to the somewhat indifferent police that she be arrested for uttering a swear word on a public street. In the end, despite his grand displays of tilting at the windmills of social ills, Dickens' utopia was bourgeois and his solutions amounted to little more than people should act nicer.

On The Hierophant card are represented two clergymen from Dickens' fiction. The first is from his last – Minor Canon Septimus Crisparkle from The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Crisparkle is uncharacteristic for a Dickens man of the cloth in that he is intelligent, sensitive, and earnestly adheres to Christ's teachings. In his name we may even see an allusion to one of Dickens' own epithets for himself, The Sparkler. The other character is the hypocritical Nonconformist Reverend Mr. Stiggins from the author's first work, Pickwick. Stiggins is an avaricious, alcoholic evangelical who shamelessly sponges off the Wellers. In him may be seen Henry Burnett, the husband of Dickens' beloved sister Fanny. Headed for a career as an opera singer, Fanny's husband initially had similar ambitions but developed religious scruples and turned against the theatre. Fanny accepted his verdict and abandoned her dreams, causing Dickens to consider Burnett with contempt, referring to him as an imbecile for his bigotry and prejudice. Together, Crisparkle and Stiggins represent the poles of organized religion. Between them lies the rose, wheel, or Catherine window of Cloisterham Cathedral, known as a bull's eye in France and an oculus in Italy. At its centre: an eye looking back at the reader, representing conscience, the eye of God, the Super-ego.

In a curious ancillary post-script to The Hierophant card, the two fictitious priests presented may also represent two real-life clergymen integral to Ellen Ternan, The High Priestess. The first is the Reverend George Wharton Robinson, clergyman, headmaster at Margate School, and Ellen Ternan's husband. The second is Reverend William Benham, later Canon, chair of Margate School Board, Dickens enthusiast, and father confessor to Ellen Robinson, née Ternan. He extracted from her the secret that she had been Charles Dickens' lover for some dozen years, a revelation he later told a fellow Dickens enthusiast who was writing a biography of their mutual idol – not ideal behaviour in a man of God, but something of a godsend for those who believe the truth will set you free. Some of what she confessed to Benham was her disgust and self-loathing at recollections of her sexual relations with the older Dickens. But then, she was a Victorian, admitting to a priest the most shameful crime a woman of her time could commit. Little could she fathom – as little as the era she lived in – that the custom and conventions of morality are as transient and mercurial as the winds, the tides, the desert sands, or any other natural phenomena.

In one sense, The Hierophant card represents man's transparent attempt to fix the moral superstructure of his sin-ravished world and set in stone his own superiority through devoutly exhibited inhibitions.

.

Notes for General Circulation :

-

The Hierophant is linked with instruction, indoctrination, power, and authority. As with all cards numbered 5 in the Tarot, it signifies conflict, the struggle to find balance in the essentially disparate realms of matter and soul.

-

The 2 clerical vignettes represent the polarities of letter of the law and spirit, male and female, active and passive, sun and moon, alpha and omega, the universal and the iota, God's omnipotence and man's free will.

-

The pontiff of traditional Tarot decks is replaced by the pope-less eye of the populace. The Papal See replaced by what the people see; a bulls-eye made of the papal bull. Some affiliate The Hierophant with the zodiacal sign Taurus, the bull. Some associate it with kowtowing, others with bullying. Some even interpret it in the colloquial sense, as a euphemism for bullshit, punctuated by the hot-air balloon emblazoned with the Union Jack.

-

The Hierophant, The Devil, The Moon, and The Sun cards share a kind of kinship; together they form a stable four-cornered cube, representing the elements, the four corners of the earth, and the foundation stones of the house of God. With the inclusion of The High Priestess card - otherwise ostracized - at the cube's centre, this 5 card family form a quincunx, as in the cinquefoil of heraldry. In this intentionally oblique manner is conveyed the idea of induction, what is shown to the pupil and what is kept hidden. In this, the clever or intuitive pupil may see the in-built contradiction inherent to esoteric understanding and institutionalized form.

-

The eye of The Hierophant is all-seeing - it both oversees all and is the small I of each individual consciousness.

-

In a traditional pattern, The Hierophant can signify the use and abuse of authority, knowledge, censor, duty, and sex.

-

Some may see in The Hierophant mortification of the flesh, denial of the self, submission, prostration, and exhibitionism. Others may detect circumcision, an all-male Eden, and the subliminal presence of the "one-eyed snake".